The Olympia Oyster, the “Oly,” the Pacific coast’s only native oyster, which has hung on narrowly the last several decades, is making a comeback thanks to a little help from its friends, including Dr. Hilary Hayford. She kindly came to the Lacey Community Center on the very cold evening of January 16th to shed light on how she and her team at the Puget Sound Restoration Fund are working their magic.

She explained that natural oyster stocks gradually became depleted first by overfishing following the colonization of North America, and then by habitat degradation and pollution. Once common from Baja, Mexico to Sitka Alaska, the Olympia oyster is reduced to approximately 40% of its prior range, and where found can be as little as 2% of its original volume. To read more about the history of the Olympia oyster refer to the companion article on this website https://protecthendersoninlet.org/the-olympia-oyster/ . In the 1920s, around the time the Pacific Oysters aka Japanese Oysters were introduced, the idea of farming oysters to try to fill the ever-increasing market demand took root. The Olympia Oyster did not take to aquaculture well, unfortunately.

In 1999 Betsy Peabody founded the Puget Sound Restoration Fund to tackle the problem of the severe decline of the Olympia Oyster. Dr Hayford’s branch of PSRF, the habitat team, currently includes Brian Allen, Jessi Florendo, Kari Inch, and Aurora Oceguera. This team focuses primarily on the restoration of the Olympia Oyster, as well as abalone, Dungeness crab, and bull kelp.

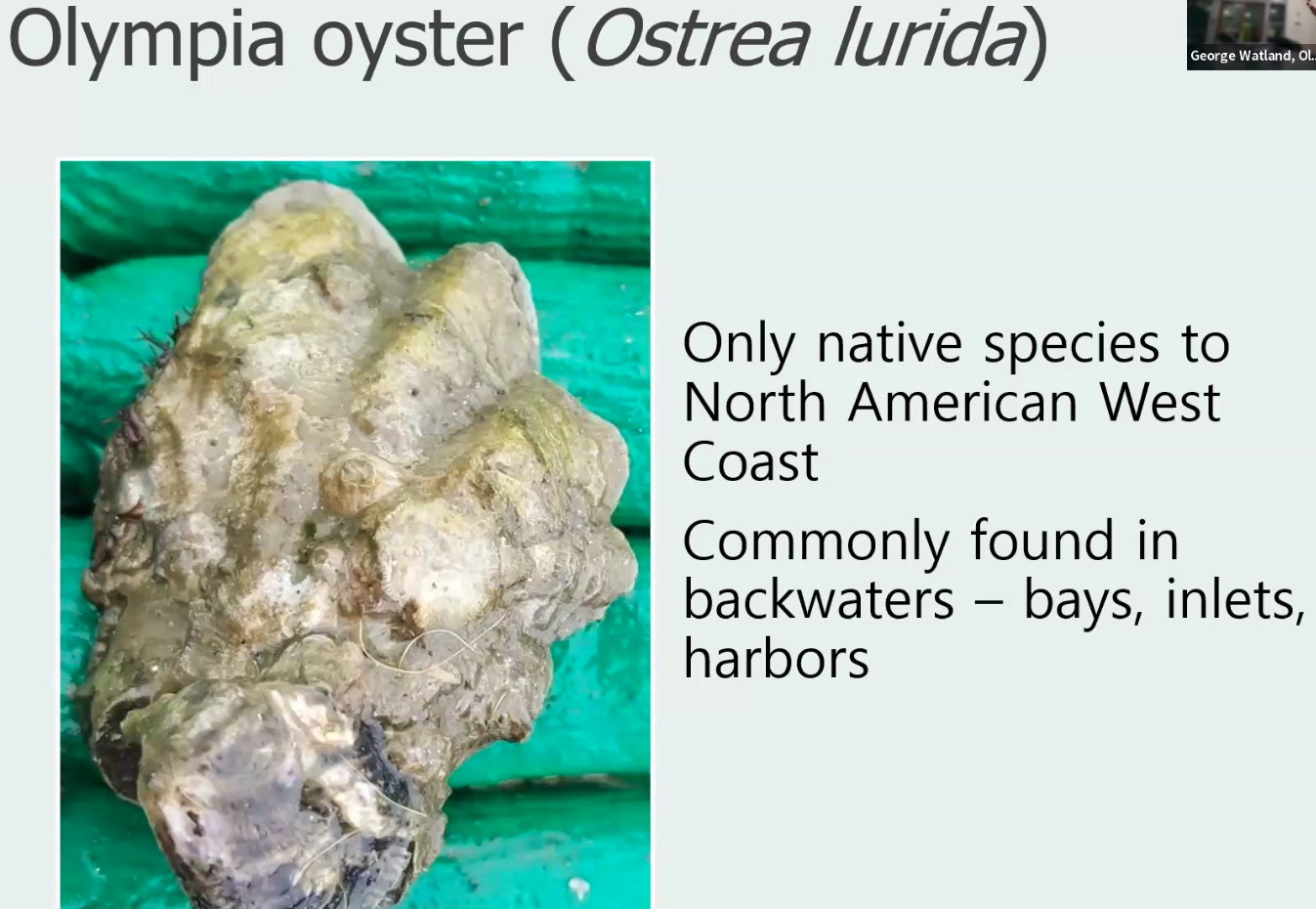

The Olympia Oyster is only about two inches across when full-grown.

![]()

![]()

![]()

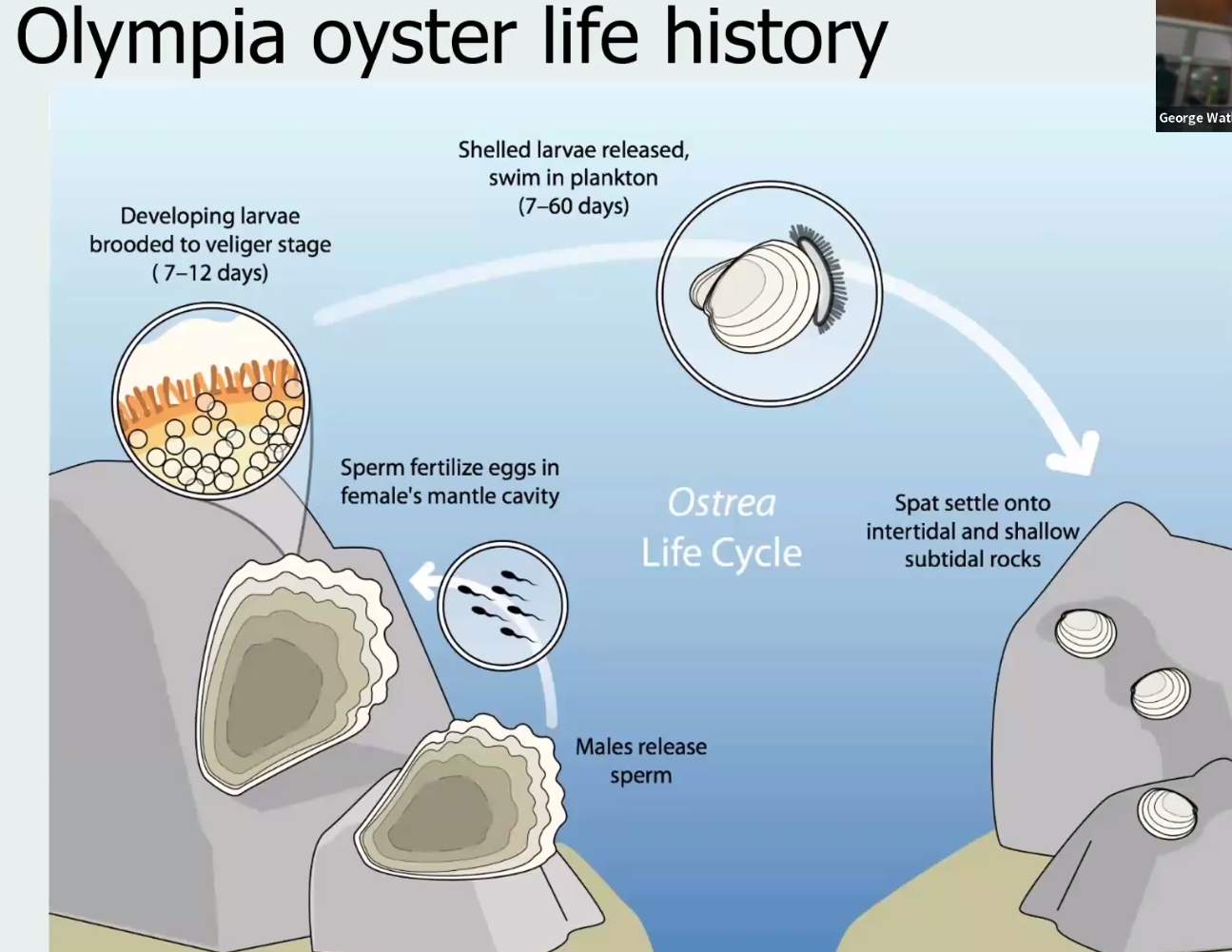

Dr. Hayford explained that the Oly’s lifespan is very interesting. It spends part of its life attached to the beach and part floating freely. The most unusual aspect is that Olys brood their larvae. They have to have the two parents right next to one another for fertilization. The larvae then stay in the animal for one to two weeks before they go out into the water for a bit before finally coming back to settle onto intertidal and shallow subtidal rocks.

![]()

![]()

When they settle, they make a very special 3D oyster reef that is distinct in that it is made up of many, many small clusters which creates a structurally complex habitat.

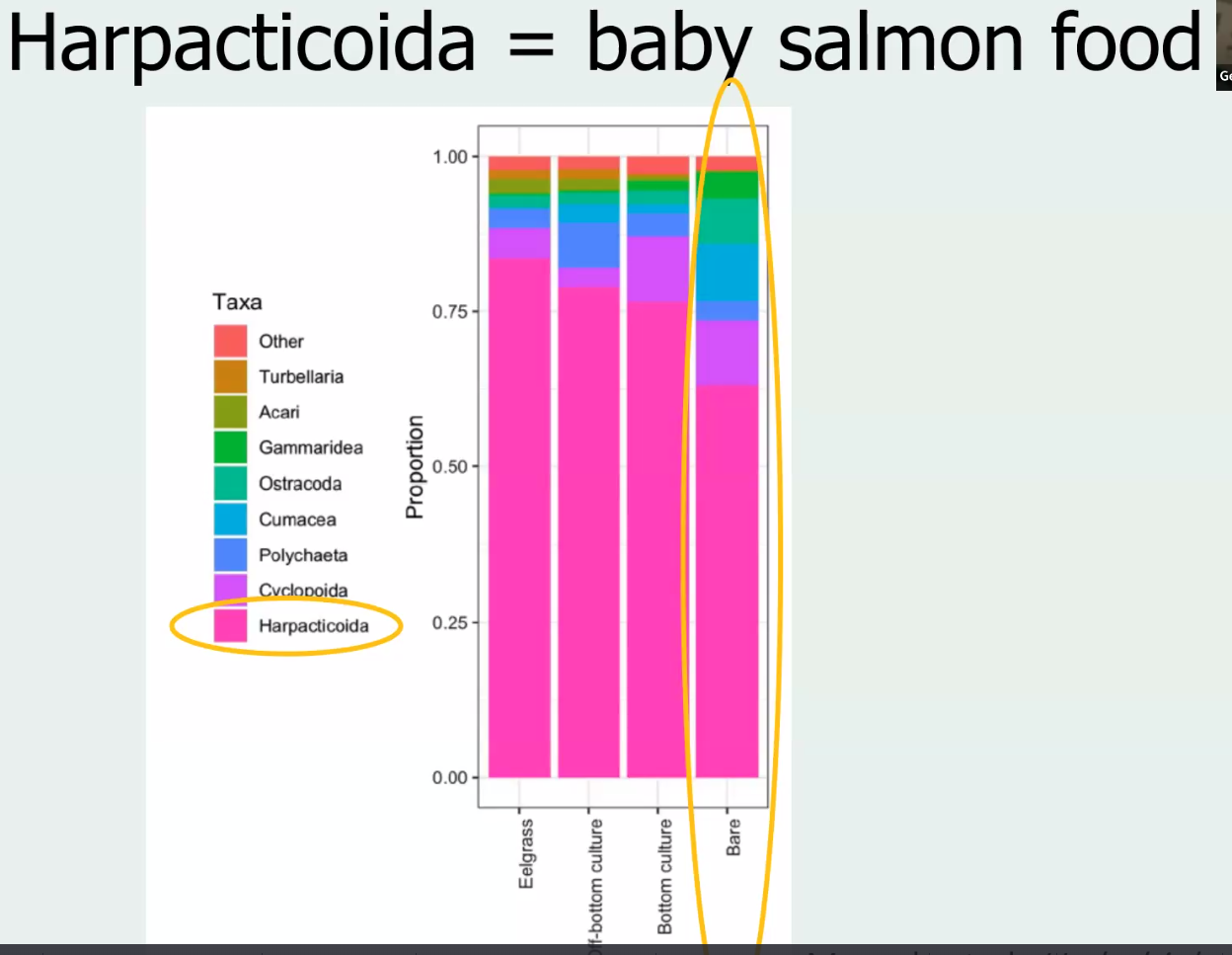

Olympia oysters are beneficial ecologically: they provide food for other animals and their habitat firms the beach. In silty mucky areas where organisms have difficulty surviving, the restoration of Olympias can firm the habitat making it more viable for other organisms to live. It is believed that since those organisms can then float on top of the mud, it leads to a more complex habitat that better harbors diverse species including salmon prey like tiny harpacticoida.

The pink areas in the next slide show that baby salmon food grows least well where the sea floor is bare, more strongly where there is bottom culture, more strongly yet where there is off-floor culture such as Olympia Oysters, and best of all in eelgrass meadows.

In areas of Olympia Oysters, there are clusters of shells and pockets of water in which to hide from the sun in low tide. Olympia oyster areas/reefs create a habitat that supports baby salmon food better than anything found so far in the team’s studies except eelgrass meadow habitat. Finally, Olys also help filter water and cycle nutrients into the sediment, but more research is needed to understand their capacity to do this which seems to be related to whether the species originated from that particular location or not.

The huge decline that happened to these great little creatures stems from factors including that they’re delicious and that they’re sensitive to pollution and shifts in land use. When this land was first colonized, they were fished without regard to completely disrupting the system. Olympia oysters were extremely abundant 200 years ago here. Since then there has been a complete crash. Their range, which is from Mexico through Alaska has shrunk 60%. In the Pacific Northwest, they are still found in 90% of their original locations, but at a greatly decreased abundance. We might see 1 or 2 or 100 oysters on a beach but not the in the amount that achieves the habitat form they’re capable of.

Besides overharvesting, pollution is a huge stressor for Olympia Oysters. Paper mills were very problematic in the South Sound. Cleaning up the water continues to be important if we hope to bring the Olympia Oysters back. Another issue is a shift in land use.

The shift in land use means a lot of different things and is associated with urbanization. One of those things is the cultivation of Pacific oysters not so much because the competition between the Pacifics and the Olys causes a problem but that when farming Pacific oysters began, huge regions were taken and restructured to maximize yield. At the same time, building sea walls and other types of structures changed our shoreline processes, creating beaches where there was a lot more muddy silt coming out which created a fundamental difference. All these human interventions happening together caused a really large crash for the Olympia oyster between 1850 and 1920 when the population took a deep dive.

When Betsy Peabody started the Puget Sound Restoration Fund in 1999, which was about 100 years after the crash, a total of approximately 100 acres of Olympia Oyster habitat locations were counted across Puget Sound. The organization set a goal then to add another 100 acres by the year 2020. That goal was achieved.

The new overall goal is to build on that great success going forward. Many different approaches are included and must consider things as varied as science, politics, and the local communities themselves.

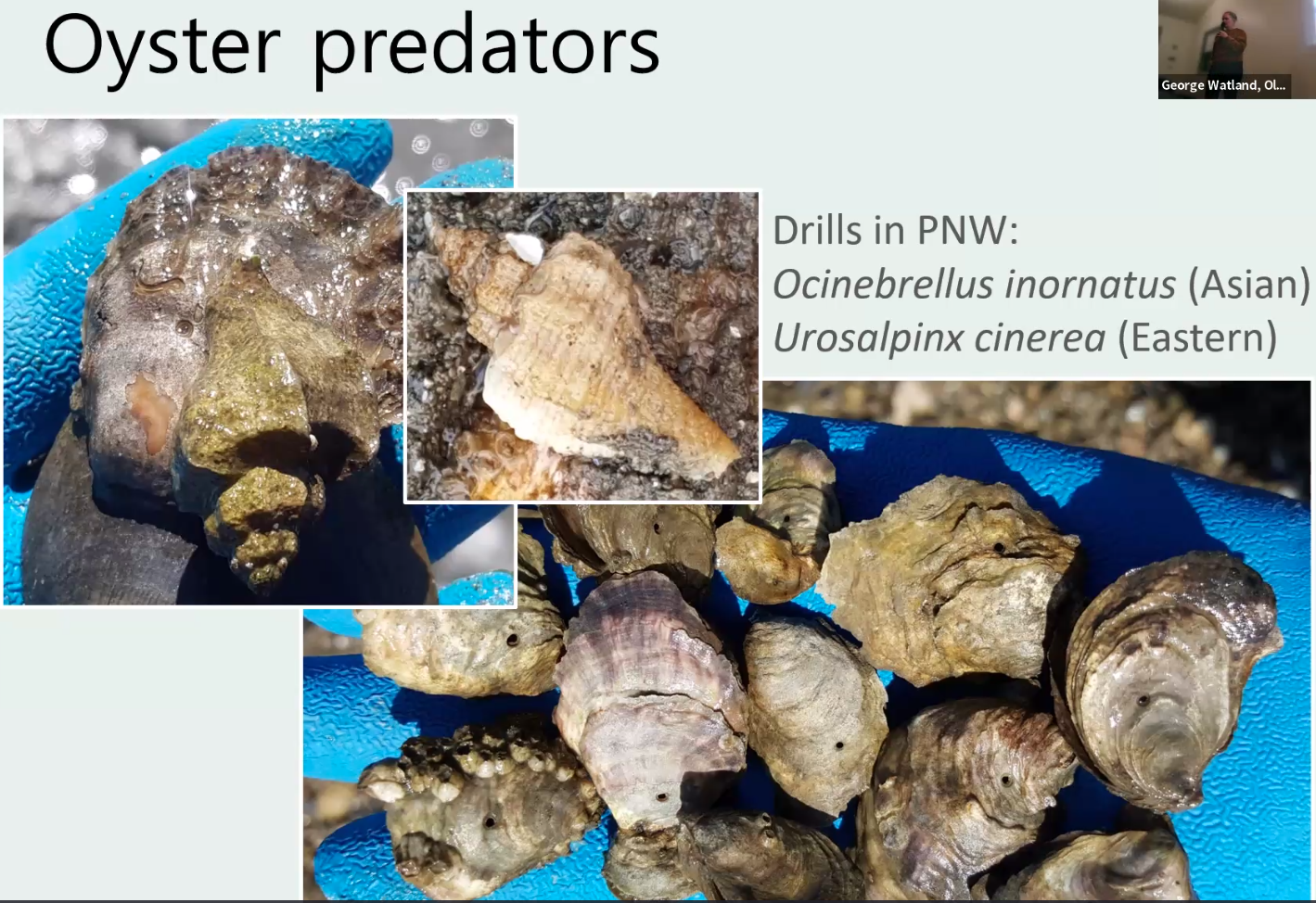

The oyster’s requirement for low pollution sometimes leads to watershed actions. The right substrate on the bottom (which can be added) must be considered. Competition and predation need to be kept in check which is turning out to be beyond what scientists can figure out very well so far. Oyster drill snails that harm Olympias came here along with non-native oysters. These tiny snails lick their way through the shell and then digest the oyster. They are voracious and can take over a whole region. They are not everywhere though, only in places where they have been brought. It can be very important when moving shell around that this snail is not brought to a new area.

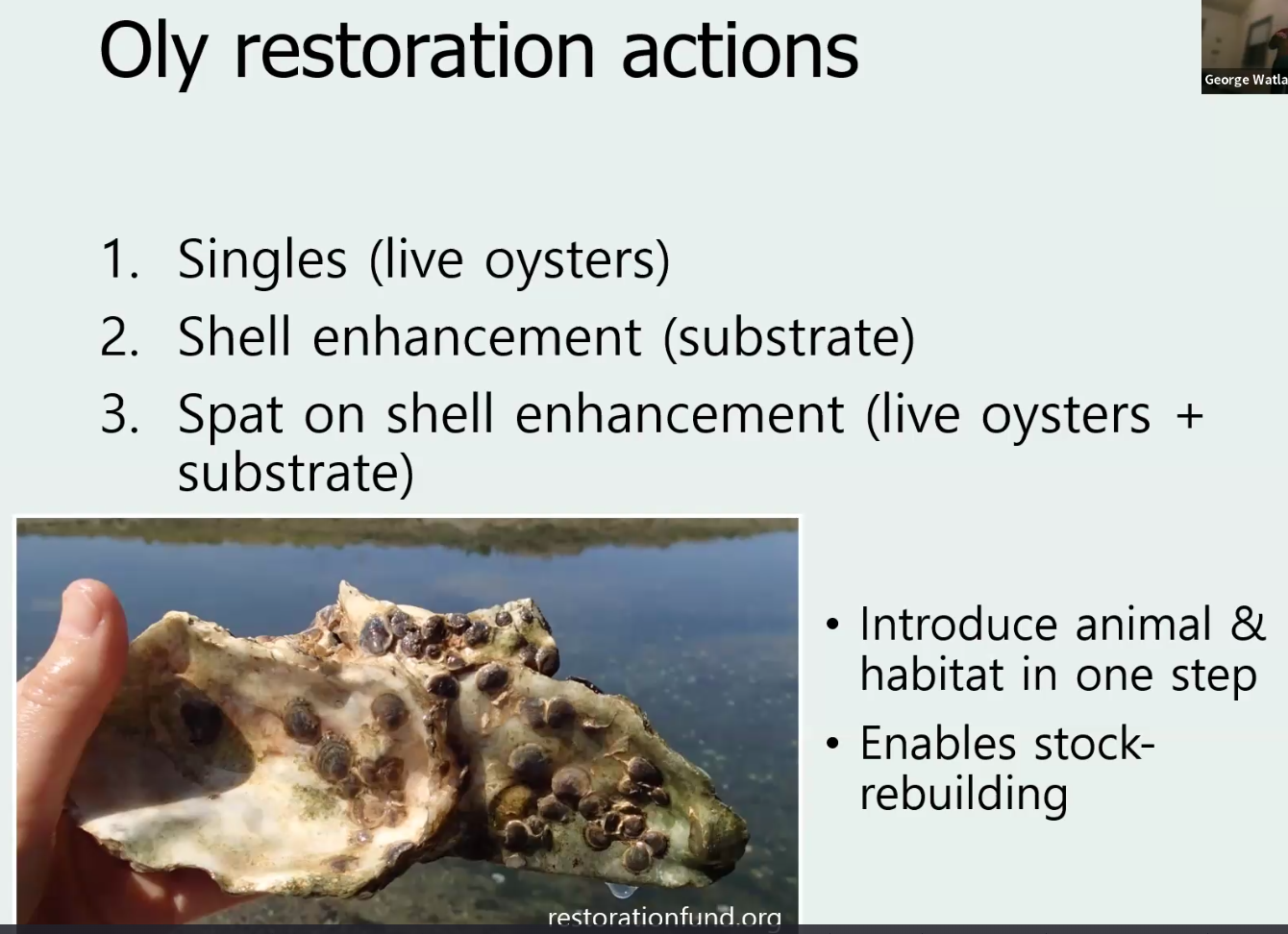

PSRF has three main approaches to restoration. The first is putting out single live oysters that are often allowed to grow a little first on the premise that the very young have a lower chance of survival. They are grown in the PSRF hatchery at Manchester, which is a NOAA lab. When the placed oysters are seen to be reproducing, a fraction of them can be harvested sustainably. This method is the most expensive restoration strategy so it’s usually used in very small areas or if there is a lot of money for overcoming one of the other obstacles.

The second restoration strategy is shell enhancement which is adding a hard substrate for the babies to grab onto. The process involves PSRF purchasing Pacific oyster shells for the Olys to settle onto, then spreading them out at a beach that has become too muddy or too devoid of hard things for Olympias to grow there naturally now, but at a beach that has babies in the water already. The scientists need to know that somewhere nearby is a source population that can populate the shell being put out. If there are babies in the water there, it is an ideal situation because it keeps the population’s genetic signal exactly the same as what’s already there. These are beaches where it’s believed there had been a high population historically.

To determine whether or not there are babies in the water, PSRF does recruitment monitoring. Recruitment is the step when the larvae come out of the water and grab onto something. For recruitment monitoring, shell stacks are used which are dowels placed upright in the beach that are stacked with cleaned Pacific oyster shells. Last year they placed shell stacks at 46 sites from the South Sound to the Canadian border. The stacks are placed from May until September and checked to see how many babies settle on them. Recruitment monitoring is happening in Henderson Inlet right now. PSRF tries to collaborate with other groups such as WDFW, which has a new Olympia oyster specialist, who might be able to assist this program going forward.

If a site is chosen for shell enhancement, A LOT of shell is involved. An example is a 300 ft barge filled with 2000 cubic yards of shells that were sluiced onto 20 acres in Dyes inlet near Silverdale in 2023. The shells are purchased primarily from canning operations or from growers who have shells from the 1980s sitting on the back lot, but the cost has been skyrocketing.

The third enhancement technique is called spat on shell enhancement. Individuals are grown in the hatchery, placed on Pacific Oyster shells, and then moved around in bags onto intermediate-sized projects. This placement allows the animal and the habitat to be restored all in one step and allows for rapid stock rebuilding. There is a spat on shell project in Samish Bay at the Taylor shellfish location funded by Amazon that PSRF works on.

The Puget Sound Restoration Fund takes most of their direction from the WDFW with which it has worked in concert with over many years. In 2012 WDFW put together a restoration guide for Puget Sound. They analyzed where historical areas were and used that to make a map of 19 priority areas. One of the 19 priority areas is in Henderson Inlet. Knowing that Olys like muddy backwater areas, Myers Point, where a Pacific Oyster farm had been operating for 100 years, and where there had been native species as well with known cultivation going back 500 years had many reasons to be chosen for ongoing spat on shell trials.

Major pollution problems happened at the end of the 1900s which was something PSRF wanted to tackle together with the former owner of Myers Point. They were able to rally a really strong response from local agencies including the Shellfish Protection Council. There was a big movement to reign in general outflow coming from septic tanks in 2005 and 06 with a lot of community buy-in about what was flowing into the back end of the inlet. The resulting actions were considered a huge success. All of a sudden oyster harvest was allowed again.

In 2011-12, the Nisqually tribe purchased the farm at Myers Point. Now, PSRF partners there with the Nisqually tribe and with WSU. As it turns out, Henderson Inlet is a place where the population of oyster drills is extremely high similar to the level found on Squaxin Island. It’s a South Sound phenomenon. It’s been proposed for people to collect the oyster drill snails to reduce the population, but one worry is that native snails might be collected accidentally. The last spat on shell count was in 2019 when there was little survival of the Olympias from one year to the next.

Some next steps: The Shellfish Protection District is vastly understaffed and seeks new board members. Additionally, PSRF believes WSU would support student or community educational programs that could involve a trial of predator snail removal. It is believed that monitoring of the spat on shell recruitment will continue there with the Nisqually tribe and will possibly expand to other areas of interest like Otis Beach with the possible cooperation of WDFW’s new Olympia Oyster specialist, Julieta Martinelli ([email protected]). One of her first tasks over the next couple of years is to revise the guidebook and its 19 areas of interest. Getting in contact with her is a good idea to find out whether your area becomes/stays as an area of interest.

More research is needed on the drill issue and how we handle predation. There are some who do not want any large shell project added to Henderson Inlet until the drill problem is solved because they believe the oyster drill problem could be exasperated by additional shells creating more habitat for the snails to hang out in. WSU has researched this issue in the past but has no current work.

At the end of her presentation, Dr. Hayford invited questions. She also welcomed further communication and shared her email which is [email protected].

Many thanks to the South Sound Group of the Sierra Club for coordinating with us on this project, for providing for the Zoom meeting, and for recording the entire presentation.

Finally, PHI has notes covering the Q & A section at the end of the meeting. Please contact us if you are interested in seeing them.

PHI thanks Tonni Johnston for this write-up.