24 July, 2023

This letter is submitted by email to [email protected]

TO: Jonathan Smith, Project Manager

U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, Regulatory Branch

4735 East Marginal Way South, Building 1202

Seattle, Washington 98134-2388

FROM: Ronald Smith, President Protect Henderson Inlet

9119 Otis Beach St NE

Olympia, WA. 98516

360-259-3789

Reference: NWS-2019-0872-AQ

Taylor Shellfish Farms

(Mazanti)

Mr. Smith and other parties:

In response to The Corp of Engineers (COE) notification letter of 19 July, 2023, note that citizens of adjoining properties and throughout Henderson Inlet believe that authorizing “the work” as your letter describes it, would be contrary to the public interest. I am the president of Protect Henderson Inlet (PHI), a 501(c) (3) non-profit organization. PHI is an alliance of interested citizens, environmentalists, scientists, and recreational users who are concerned about current and expanding aquaculture in both the nearshore environment and public waters, and its impact on aquatic plants, animals and ecological function. Please enter this document into the public record and consider it to be both my opinion and the opinion of the organization.

We request that the COE not issue a Letter of Permission (LOP) or an individual permit under section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act for this project. Further, we request a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Mazanti Taylor project site based on many factors, but especially because of its unusually exposed footprint which makes it at high risk for loss of geoduck plastic to the environment. See details on pages 15-17.

Introduction

Protect Henderson Inlet (PHI) does not oppose all aquaculture; however, more environmentally safe methods are needed in commercial aquaculture to protect our marine waters, and these methods will certainly be found when commitment is made towards proper research. PHI recognizes that oysters and other non-geoduck clams have been cultivated in northwest waters for thousands of years; we recognize the rights of indigenous peoples to continue that tradition. Likewise, there is a 100+ year history of non-tribal oyster cultivation in Puget Sound that should be allowed to continue, with recognition of cumulative impacts and the limits of our ecosystems as well as the ongoing investigation of more environmentally friendly practices.

PHI is not opposed to the cultivation of geoduck for sale, but is strongly opposed to the current methodology. Cultivation involves massive implantation of plastic tubes into the beach, dense planting of hatchery stock, and liquification of the beach for harvest. Based on review of the available science, we believe this methodology to be unsound and sorely understudied. There simply is not enough quality science to justify this very new and explosively expanding cultivation method.

I am a scientist. I have a Bachelor of Science in Biology which included marine studies and a Doctorate of Medicine. Based on my decades of experience in evaluating scientific studies, I will describe in detail the reasons why Taylor’s claim that “impacts from geoduck farms would be insignificant” is a false claim made by lawyers and business administrators, not scientists.

Summary

Taylor Shellfish wrote a letter to the Thurston County Planning Office of 31 January, 2023. In that letter, Erin Ewald of Taylor Shellfish asserts that scientific research supports their method of geoduck aquaculture, assertions that Taylor Shellfish has falsely claimed on many previous occasions. In fact, science does not support their claims. The environmental impacts of geoduck aquaculture vary from highly significant to unknown, but never insignificant as Taylor would have you believe. This document outlines the campaign of Taylor Shellfish to mislead the permitting authorities about the environmental impact of their geoduck methodology; Taylor has previously been highly successful in convincing the Corp of Engineers (COE) to allow its substantial developments. Their past administrative successes should not prevent the COE from taking a fresh look at the science and making an independent assessment.

Before delving into the details, consider this: in the “big picture”, the ideal benefits of allowing this permit could be jobs, food for the locals, tax revenue, and profit for the business. Unfortunately, Taylor hires mainly low-wage employees for this back-breaking beach work and even had to settle a case of racial discrimination in 2017. https://www.eeoc.gov/newsroom/taylor-shellfish-pay-160000-settle-eeoc-racial-harassment-suit

Taylor will pay almost no local taxes for this site. They will produce virtually no local food now that they have removed Manila clams and oysters from the permit application; the entire geoduck crop will be exported. The owners do stand to make a profit of somewhere between 1 and 2 million dollars per acre every 5-7 years. That’s not illegal, but what do the citizens get for the use of their public resource, the nutrient-rich water of Henderson Inlet? The answer is virtually nothing. Worse than that, we the citizens bear the risk of degradation of our ecosystem from Taylor’s actions.

There are many more arguments that can be made against the granting of this permit. Pyke Johnson, a local resident near the proposed site makes an eloquent argument based on human needs in this King 5 news report from 11 July 2023:

David Hall will lose access to the beach where he has sponsored natural marine education for thousands of students, as outlined in this article in The Olympian on 10 July, 2023

https://www.theolympian.com/news/local/article277117643.html

David’s property at 9505 Johnson Point Loop NE, Olympia, WA 98516 directly adjoins the Mazanti Taylor site. As a board member of PHI, he opposes the permit.

There are many conflicts with the goals of the Shoreline Master Program that have been pointed out by citizens in letters to the County. There is a significant conflict between the existence of the special taxation district of Henderson Inlet and the granting of unlimited utilization of our clean water by Taylor Shellfish, which does not participate in our financial obligation to ensure clean water. Arguments against this permit are being made by many citizens, and I urge you to give consideration to all of them.

This response will focus on the specific errors that Taylor Shellfish makes in the use of science to try to substantiate their arguments. Especially important in this regard is an analysis of the Geoduck Aquaculture Research Project (GARP) report and the environmental concerns raised by that report. The COE should reevaluate its assessment of the science, especially the GARP report, and should not permit Taylor Shellfish to expand geoduck aquaculture to the Mazanti site in Henderson Inlet.

Why no further geoduck aquaculture permits should be granted until further research is performed.

- Lack of sufficient scientific research into geoduck harvest methods, obscured by misinterpretation and misapplication of the findings of the GARP report by Taylor Shellfish.

- Massive use of plastics not proven safe for the environment with an especially high risk of loss to the environment at site 2022103702.

- Near complete ignorance of the genetic effects of hatchery geoduck on wild stocks, in spite of warnings in the 2013 Sea Grant Geoduck Aquaculture Research Program report (GARP).

1: The GARP Report

What is GARP?

The technique of geoduck aquaculture was developed by University of Washington scientists in the 1990s and subsequently given over to industry which implemented commercial applications. By 2007, there was significant concern about the potential impact of geoduck aquaculture, which is done by implanting plastic tubes containing hatchery juveniles and later liquifying the beach with hydraulic jets to excavate the adult clams. The legislature mandated investigation because of the invasive nature of the methodology, and it commissioned the University of Washington to review the scientific knowledge base and come up with recommendations. Based on UWs review, the legislature stipulated the evaluation of “key uncertainties” and 6 priorities were established. Results were to be published before the end of 2013. The reader is encouraged to carefully read this report, the major elements of which are only 11 pages.

What did they do?

UW Sea Grant authorized studies for only three of the six “required” priorities, which were to look at the questions of 1) the effects of structures used in geoduck aquaculture 2) the effects of commercial harvesting 3) naturally occurring diseases and parasites in the existing geoduck population. They did recruit additional science already in progress to look at genetic interactions between cultured and wild geoducks addressing a 4th priority. They did not reproduce that actual research in the report, but made significant recommendations based on thorough review of those studies. The other two questions pertained to the extent of alteration of waters overlying a geoduck site and the impact of sterile triploid geoduck hatchery stock were simply not addressed. Why not?

What did it cost?

Total cost was $1,550,357. For this, the taxpayers got three peer-reviewed scientific studies and analysis of a fourth.

What did the studies show?

The GARP funded scientific study with greatest impact on aquaculture was Resilience of Soft-Sediment Communities after Geoduck Harvest in Samish Bay, Washington authors Horwick and Ruesink of UW. They evaluated the response of native eelgrass to geoduck aquaculture using reference plots to compare before and after effects. The findings were dramatic with 44% reduction of eelgrass after harvest and complete loss 1 year later. Equally important but now completely ignored, is that the authors noted post-harvest decrease in abundance, richness, and diversity of other species which they could not explain solely on the basis of loss of eelgrass biomass. They suspected additional impacts were present beyond those on eelgrass, and suggested further research. Because of these findings, eelgrass surveys are required for all aquaculture permits, but no follow-up based on the authors’ suspicion of more extensive effects of geoduck aquaculture has been done that I am aware of.

The study Ecological Effect of the Harvest Phase of Geoduck Clam Aquaculture on Infaunal Communities in Southern Puget Sound, Washington was eventually published in the Journal of Shellfish Research in 2015. The 2013 GARP report includes a pre-published version. It is important to read the actual published and peer-reviewed scientific paper, as there are many important details that are not evident from reading this GARP summary. The authors conclude that 1) the sites of the study were so diverse that it limited the ways they could look at their data. 2) They didn’t see a statistically significant numbers reduction or decrease in biodiversity from geoduck aquaculture harvest 3) They didn’t see a statistically significant spill-over effect on adjacent plots.

These findings are stated out of context in the Taylor letter and do not appear in the conclusions of the GARP report. A major problem with this study is that it appears to ignore some of the data, and it lacks statistical strength. The study only looked at 10 of 50 species, essentially ignoring the rest. Of those 10, 3 (30%) were significantly diminished in number, although those species did not “approach local extinction”. They did not identify a “sentinel species”, one that could be followed to assess the overall health of the ecosystem. These kinds of limitations are common in early research, and it is normal to expect that additional work will be needed. This is why the GARP report in its conclusions, called for cumulative studies. Unfortunately, the follow-up work was not done. You may see a more complete review of this article including a link to the full-text version in Appendix A, critique 2.

The next study considered is Effect of Geoduck Aquaculture Gear on Resident and Transient Macrofauna Communities of Puget Sound, Washington published in the Journal of Shellfish Research in 2015. It concludes that geoduck aquaculture significantly affects the abundance, but not the biodiversity of species at the site. This paper has very similar problems to the first one in that it analyzed only 12 of 68 species identified. The research did not even include an assessment of the harvest phase. The paper is appropriately self-critical, describing how it is limited because it did not assess cumulative effects, was not designed to include salmonids, and suffered effects from “seasonal biofouling by macroalgae” on geoduck hardware. In the abstract, the published paper calls itself a “first look” and calls for further studies. Again, these limitations are expected in early research, but that doesn’t allow science to skip the follow-up. Please see a more complete critique here with a link to the complete published paper in Appendix A critique 1.

The last GARP funded study about parasites Characterizing Trends of Native Geoduck Endosymbionts in the Pacific Northwest eventually published in The Journal of Shellfish Research is basic research that may someday prove helpful. They describe newly recognized parasites and say that it’s good to know about them in case there ever is an outbreak, but doesn’t make any predictions or offer recommendations about risks of parasites in cultured geoducks on wild stocks.

How did the GARP report summarize its conclusions?

When I review the two-page section 4 of the GARP report “Research Priorities & Monitoring Recommendations”, it makes me wonder if anyone actually read it.

The very first defined research priority is “Cumulative effects of geoduck aquaculture”. The highest priority recommendation was for further research to see if keeping a geoduck aquaculture site in one place or adding others nearby had a significant effect. They recommended developing predictive models “1) to evaluate direct and indirect ecosystem effects in scenarios involving future increases in the extent of geoduck aquaculture and 2) identify appropriate indicator species that reflect the broader status of ecosystem health in response to geoduck aquaculture expansion.” Have either of these been done? 10 years later, NO. The report does NOT conclude that geoduck aquaculture is environmentally safe, although specific elements of the report that may seem to say so are often cited out of context.

Equally important, Section 4 goes on to raise major concerns about the effect that hatchery geoduck plantings may have on wild geoduck stocks. By planting millions of hatchery juveniles, the potential to adversely affect the genetic pool of wild stocks was thought possible. These are two studies published in this timeframe, presumably the source for the report, but not specifically stated:

Maturation, Spawning, and Fecundity of the Farmed Pacific Geoduck Panopea generosa in Puget Sound, Washington, Journal of Shellfish research, Vol 34, 2015

Reduced Genetic Variation and Decreased Effective Number of Breeders in Five Year-Classes of Cultured Geoducks (Panopea generosa), Journal of shellfish research, Vol 34, 2015

The first study found that cultivated geoducks are capable of spawning within 2-3 years of planting and could certainly mix with natives. The second study recommended procedures to increase genetic diversity in hatchery stock and suggested that the use of triploids should be considered to protect wild geoduck populations from genetic impact. Neither study suggests that the wild geoduck population is free from the risk of genetic alteration from hatchery stock. This is the same scenario that led to reduced survival of wild salmon because of the rearing of hatchery fish.

Back to the GARP report – referring to reproductive contribution from geoduck farms, it states “almost nothing is known about settlement of juveniles”. They further go on to say “investigating triploid geoducks is critical for understanding the extent to which triploidy could help prevent genetic change to wild stocks”. For those unfamiliar with the term, triploidy refers to a genetic modification which renders the clam sterile.

The GARP report outlines great concern for a genetic impact on wild geoduck from hatchery stock, yet 10 years later this question is unresolved. We do see rapid expansion of commercial geoduck farming with seemingly little concern for its potential harm.

GARP Critique Summary

Although industry claims that the GARP report supports their methods of geoduck aquaculture, it actually does nothing of the kind. It raises more questions than it answers.

The GARP report gave strong evidence of the detrimental effects of geoduck aquaculture on seagrass and raised suspicion that effects on the environment were greater than on just eelgrass. Researchers recommended that these other possible effects should be investigated.

Although genetic studies about the potential impact of hatchery geoduck on wild stocks were not obtained within the program, the compiling scientists of the GARP report assessed outside scientific studies and recommended both caution and further investigation.

The studies about planting and harvest techniques included in the GARP report are described by industry as definitive for establishing geoduck aquaculture as safe for the environment. On detailed review, these studies are significantly limited and do not have the scientific weight necessary to substantiate the marked expansion of geoduck aquaculture that has taken place since 2013. We simply do not know many of the answers. In particular, the strong recommendation to obtain cumulative, long-term studies has not been met. At best, the studies suggest that the beach is pretty resilient and might recover from insults if allowed. There are currently no requirements for requiring a permitted beach to remain fallow for recovery.

A reasonable question to ask Is why UW scientists aren’t speaking up about the shortcomings of the GARP report. I don’t know, but I speculate that it’s because the State legislators spent significant taxpayer money and expected to get a definitive answer; UW scientists did what they could in the 6 years given, but it wasn’t enough time to answer all the questions. Politics being what it is, nobody wanted to say that the job would take more time and more money. UW certainly doesn’t want to say they didn’t get the job done (btw, they didn’t get the job done). UW has the prestige of housing the “Sea Grant” people, their research programs benefit from that and I’m sure they wouldn’t want their status to be impacted. Moreover, the industry has convinced government that aquaculture is vital to our future (useful, not vital). Repetitively making untrue assertions about the GARP study, Taylor tries to make them into fact. It is unfortunate that the same UW scientists whom we should be relying on to correctly explain the science to citizens and government, and to stand-up for the environment, are silent.

Finally, it should be noted that one of the major concerns of environmental activists, plastics in the environment, was not a priority at that time and was not even mentioned in GARP. The following section was written in response to false and misleading information conveyed to the Thurston County Planning Commission.

2: Plastics in the Environment

The shellfish industry argues that “Plastic Aquaculture gear is not a threat to Puget Sound” in a paper submitted to the Thurston County Planning Commission during the commission’s review of the Shoreline Master Plan in 2021. A copy of that document is available for review.

This paper makes many false and misleading statements and is reviewed in detail here. Each of the “Items” listed below is a false statement made in that paper written by Ramboll Environ US Corporation of Seattle Washington, who is a paid consultant for Taylor Shellfish.

Item 1.2 – “Aquaculture operations are not a significant source of marine debris.”

Aquaculture is a huge source of marine plastic in the environment and the use of the term “debris” is misleading. This plastic is intentionally placed, and present in the environment for many years while being used by the industry. Some of it certainly becomes debris when it is lost. Plastic impacts the environment no matter how you label it.

How much plastic are we talking about? One foot of 6 inch PVC pipe weighs 3.53 pounds. Taylor shellfish would plant 146,000 of these tubes in the Mazanti-Taylor beach, each about 1 foot in length, a total of 73 tons of plastic. The claim that they will recover much of it is misleading. The industry typically reuses this plastic for as many 2-year cycles as possible, and by its own admission plans to use it for decades. The County should consider that by granting this permit, they are in-fact allowing the permanent placement of many tons of plastic in the environment. All of the plastic is subject to degradation and some will certainly become debris. Bill Dewey sidesteps the question of plastics by claiming that they now use HDPE mesh tubes. While they are at times using those tubes, (which, while more resistant, do also degrade in spite of his claims), they have a great store of used PVC, which they continue to reuse and stockpile on their properties. Their Lockhart Property on Henderson Inlet was replanted in 2023 with PVC pipe. Please see below photograph.

The industry admits that plastics in the environment is a major problem, and cites literature about sources of plastic pollution. They are correct that terrestrial sources are the major contributor of microplastics in the environment. No argument. However, it is completely disingenuous to suggest that because indirect terrestrial sources are a major source of plastic pollution, that the county should permit the direct placement of tons of plastic in the environment. The industries’ argument here has absolutely no merit.

The industry states: “loss of aquaculture gear is already minimized.” What does this mean? They never claim to recover all the plastic, but give no data as to how much is lost. And they do lose it. Anyone who lives near an aquaculture site is used to having plastic aquaculture gear wash onto their beaches. On Otis Beach, where I live, it happens all the time.

In a separate letter, I’ve already characterized the dynamic nature of the proposed geoduck site with potential for 4 foot storm waves from two directions. The industry should define “minimal”. What percent of lost tubes do they expect? In the unlikely event that they recover 99% of their tubes, that leaves approximately 1500 tubes (5,295 pounds) in the environment, which is highly significant. To the best of our knowledge, Thurston County has no plans to enforce a standard of tube recovery, nor do they have capacity for compliance assessment. It is irresponsible for the County to permit this process. Furthermore, the authors of Taylor’s pro-plastics paper intentionally misstate the science when they say: “studies have shown that removal of marine debris is effective at mitigating the potential to create microplastics. (Andrady 2011). This is the actual abstract of this citation with highlights:

“2011 Aug;62(8):1596-605.

doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030. Epub 2011 Jul 13.

Microplastics in the marine environment

Affiliations

- PMID: 21742351

- DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030

Abstract

This review discusses the mechanisms of generation and potential impacts of microplastics in the ocean environment. Weathering degradation of plastics on the beaches results in their surface embrittlement and microcracking, yielding microparticles that are carried into water by wind or wave action. Unlike inorganic fines present in sea water, microplastics concentrate persistent organic pollutants (POPs) by partition. The relevant distribution coefficients for common POPs are several orders of magnitude in favour of the plastic medium. Consequently, the microparticles laden with high levels of POPs can be ingested by marine biota. Bioavailability and the efficiency of transfer of the ingested POPs across trophic levels are not known and the potential damage posed by these to the marine ecosystem has yet to be quantified and modelled. Given the increasing levels of plastic pollution of the oceans it is important to better understand the impact of microplastics in the ocean food web. “

As you can see, the paper does not say that it is environmentally sound to permit the placement of 73 tons of plastic into the marine environment, no matter what percent of that is actually lost and subsequently recovered.

This is a typical misuse of science by the industry. Their article really is an indictment of the process of geoduck farming.

Item 1.3 – “Aquaculture gear does not break down easily to form microplastics.”

The industry does not assert that aquaculture gear does not break down – they admit that it does. “Easily” is a qualitative term. Mechanisms for breakdown are well documented, indeed clearly stated in their own references (see above). “Weathering degradation of plastics on the beaches results in their surface embrittlement and microcracking, yielding microparticles that are carried into water by wind and wave action.” These mechanisms include degradation by UV light, heat, mechanical abrasion by contact with beach substrate and breakdown by microbial agents. The argument that aquaculture plastics are not exposed to UV light is patently false. While they are somewhat protected due to being submerged part of the time, these tubes are stored in direct sunlight when not in use, either on floating barges or in piles on Taylor Shellfish properties where they are extensively exposed to light and heat.

Barge with used PVC tubes stored in Henderson Inlet for months, replanted on the Taylor Lockhard geoduck site

Furthermore, any lost tubes washed onto shore away from the monitored site may be exposed for years. Residents in the area of shellfish farms often have a collection of such gear that has washed up.

Plastic debris washed up on the beach at Ron Smith’s residence

There is no consideration given for the effect of mechanical abrasion on the plastic. If you have any doubt about the harshness of the beach environment, all you have to do is try to walk barefoot on the beach in question. The substrate shifts constantly. On my nearby beach, I have seen the volume of gravel change by as much as 1 foot in depth in as little as a week.

The authors of this plastics paper make the argument that the presence of plastic debris in the environment from sources other than aquaculture makes the placement of the shellfish industry’s plastic irrelevant. It is their argument that is irrelevant.

Item 1.4 – “Microplastics have not been shown to affect Puget Sound biota”.

Seriously? Do a quick web search for science articles about the effect of microplastics on marine life and you will be overwhelmed by the number of articles. There are now studies showing it to be a global problem, and all of our estuaries are impacted.

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/tracking-global-marine-microplastics

I do agree with the authors that polystyrene spheres are not the most common polluting form. However, while discounting spheres because they are not the breakdown product of their plastic, they ignore the capacity for their plastic to degrade into microfibers, which is the most common form of plastic pollutant. While arguing that our Puget Sound waters are still relatively clean compared to some other places in the world, they seemed to think that adding to the problem is all right. It is not.

Item 1.5 – “Use of rigid PVC tubes do not pose a toxic hazard.” In this section, the authors state that the PVC pipe used by the shellfish industry contains no phthalates, but offer no reference to the actual pipe used or the chemical constituents of that pipe. There are numerous additives in all PVC pipe. Should they not submit documentation of what they intend to use? Should we accept this statement at face value as if from an uninterested party? Wikipedia states that it (PVC) “always requires conversion into a compound by the incorporation of additives such as heat stabilizers, UV stabilizers, plasticizers, processing aids, impact modifiers, thermal modifiers, fillers, flame retardants, biocides, blowing agents, smoke suppressors and (optionally) pigments.” How many of these additives are used in their pipe? Are we supposed to believe that they commission a special pipe low in some additives because of their marine use? They do not say so, but in some documents (DEIS Burly Lagoon 2023) they claim to use “marine grade” plastic. I have tried doing a web search for “what is marine grade PVC”. See for yourself. You will find no coherent description of this as a special product, and it seems to be simply ordinary Schedule 40 PVC.

Item 1.6 – “HDPE gear also does not pose a toxic hazard.” They state “few studies” as being available, but go on to state 1.6% loss of HDPE by weight in 12 months. Let’s just do the math based on the weight of plastic for the proposed Johnson Point project. So, it’s OK to put plastic in the beach that leaches 13,245 pounds of chemicals and/or microplastics in a year? How can this be a serious argument? Their final line is “Lack of degradation of HDPE gear is supported by the decades of use of aquaculture cages reported by Puget Sound growers.” No science there, but a clear admission of intent to keep using the product forever in spite of evidence that it degrades.

Item 1.7 – “Microplastics are not a major source of exposure to persistent organic pollutants (POPs).” The authors restate the known pathway of migration of microparticles which have an affinity for POPs, and then assert that because POPs are absorbed into sediments that it somehow doesn’t matter. And, they say that there really isn’t any good data anyway. What is important here is that marine organisms ingest microplastics, which have an affinity for POPs, thereby incorporating them into their tissues. As this moves up the foodchain, it eventually reaches the top of the chain which includes humans and orcas. If POPs are also absorbed into sediments, it doesn’t make the foodchain problem any better. Their argument is irrelevant and only distracts from the main issue.

The conclusion of the paper continues to systematically misstate the facts. I would rewrite the conclusion thus:

Aquaculture operations are a significant source of marine plastic pollution and, although the products used are fairly robust, they do degrade. Based on the massive bulk of plastic embedded in the beach and the extended lifespan of its use, degradation is inevitable, and the amount of microplastics added to the environment is highly significant. The argument that, because the larger portion of marine plastic pollution is secondary from terrestrial sources, makes the intentional addition of many tons of plastic to our waters (even intermittently) absurd.

And, as to the effect on Puget Sound biota as being negligible, there is growing alarm in the scientific community about the dangers of microplastics. The advocates for plastic use in the marine environment would rather wait until the impacts are obvious to everyone. When the impact on marine biota is widespread, it will be too late. The opinion of the European Union in a recently published 300-page study suggested a “precautionary” approach.

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e9e7684a-906b-11ec-b4e4-01aa75ed71a1

It would seem the logical thing to do to wait for more data and restrict marine use of plastics until they can be shown to be safe.

If you wish to read more about the threat of plastic in our environment, please visit

https://protecthendersoninlet.org/the-threat-of-plastics-in-our-environment/

where there is a more general discussion.

Now that the real risk of plastics in the environment is outlined, what about the specific risk of putting huge quantities of plastic tubes at the Johnson Point site?

The choice of this site for geoduck aquaculture should be closely scrutinized as it represents a potential disaster from loss of plastic to the environment. This should be considered in the Environmental Assessment and a full Environmental Impact Statement should be obtained.

Please consider these details carefully:

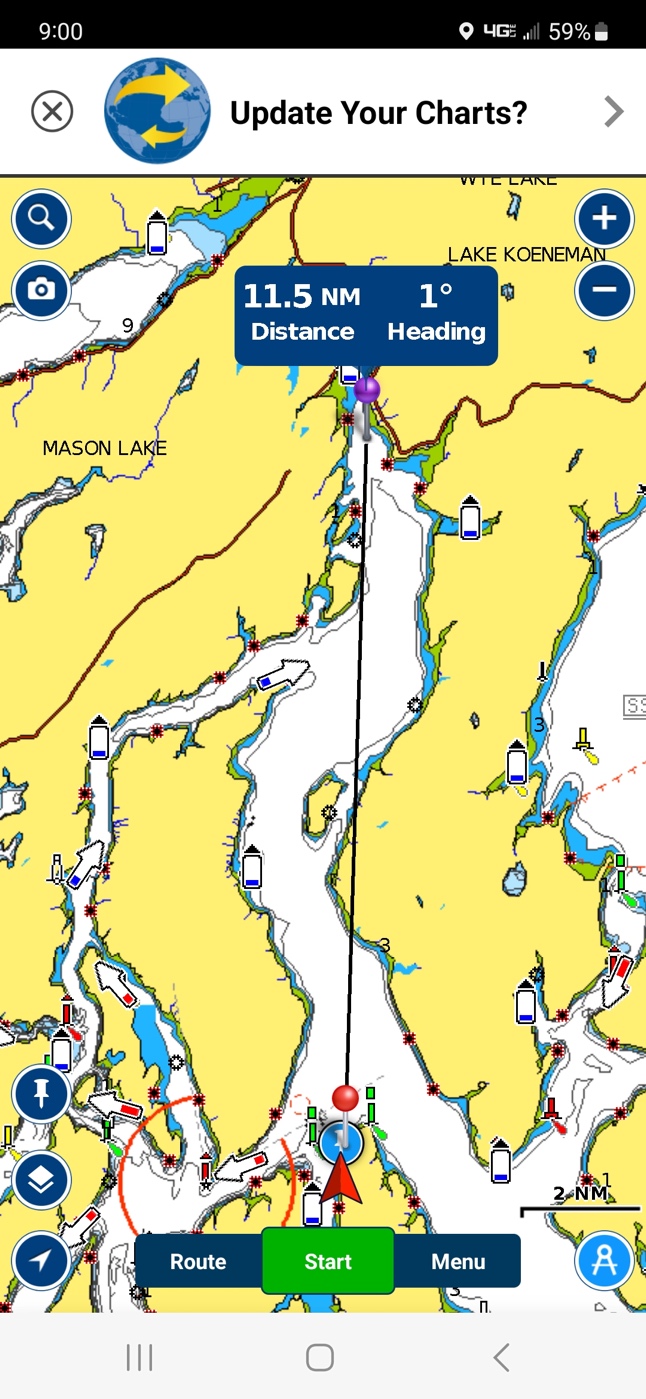

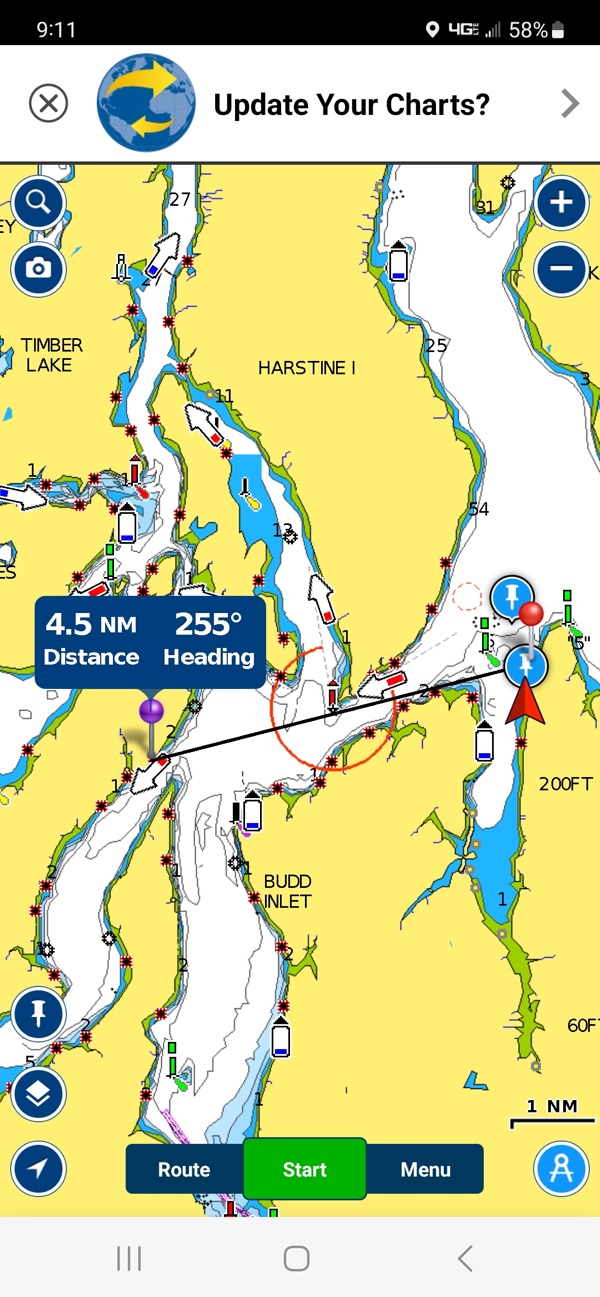

This site is unusual compared to other projects where geoducks are farmed because of its extreme exposure. Please refer to the attached marine maps.

To the north lies Case Inlet, where there are 11+ miles of open water continuous with the proposed site. To the west lies Dana Passage where there are 4.5 miles of open water.

Local sailors are well aware of the funneling effect of the marine bluffs on wind, and residents know that storms do create pronounced wave action on this beach.

In our most common storm from the southwest, the site is only mildly exposed. However, in storms from the west or north this beach is directly impacted. When there is 40+ knot wind, the beach is thrashed with waves up to 4 feet. We have winds of 20+ knots many times through the year, probably every week, and you can see what a small amount of wind does in this video.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIWvjI9i9-w

Note also in the video the various aquaculture debris on the beach from local commercial shellfish operations.

While severe storms are less common, they typically do occur several times a year, frequently coming from the west or the north. I live 1/4 mile south of the proposed site, and I have personally witnessed winds over 60 mph.

David Hall is a resident whose property adjoins the Mazanti-Taylor site. You will find his letter opposing the site in the Department of Ecology comments file. David has a lot of experience growing oysters on this beach, having sponsored 3-4 thousand student visitors during the last couple of decades. This has been in collaboration with South Sound Green, an educational program that has taught students about beach ecology, including a program on oyster growing. (By the way, this beach that has been used for decades for this program will no longer be accessible if this permit is allowed).

David has learned that oysters can only be grown in bags because loose oysters are rapidly dispersed by waves and currents. We on Johnson Point and Otis Beach are used to finding stray oyster bags from commercial shellfish operations across the inlet washing up on our beaches (see photos). We realize that Taylor likely can use robust methods to secure oyster bags (they will have to do so). However, it is highly unlikely that individual geoduck tubes can be adequately secured in the beach against a pounding 4-foot surf. Given the plan of planting 150,000 unsecured tubes in the beach (10 tubes/m2 x 4047 m2/acre x 3.6 acres = 145,692), there is the potential for a disastrous result, with plastic tubes scattered for miles. Please also be aware that currents along this region of South Puget Sound are strong in nearby Dana Passage which is listed in the top 7 channels of Puget Sound for current speed (Encyclopedia of Puget Sound).

Taylor has previously submitted letters to the County Planning Commission (during the revision of the Shoreline Master Plan in November 2020) indicating that they have a plan for collecting lost tubes from their geoduck planting sites. It seems reasonable that they could collect errant tubes that wash up on the beach after a storm if they were prompt in their actions, but it seems unlikely that they could recover a significant number of tubes lost in deep water, which would require extended time with SCUBA gear traveling well beyond the borders of the site. It is my understanding from talking to a prominent South Sound grower that geoduck operators typically dive their sites only about once per year.

Let’s think about this: If Taylor lost only 1% of its tubes in a severe storm, that would be 1,500 tubes, roughly 7,500 pounds of plastic! Even loss of 0.1% (150 tubes) might be beyond the capability of a dive crew to recover. In reality, we really don’t know how many tubes are lost because there is no compliance monitoring by Thurston County, and the shellfish companies don’t report it. Certainly, the county would not issue me a permit to dispose of this volume of plastic waste in the marine environment.

The bottom line: Permitting for this site should be denied based on risk to the environment from lost plastic which is now being globally recognized as a major threat.

Please see discussion on www.Protect Henderson Inlet.org for the real risk this plastic poses.

3: Genetic Risk to Wild Geoduck Stocks

This topic has been discussed thoroughly in the critique of the GARP report. Let me add that I have discussed the subject of genetic risk from current hatchery geoduck practices with Dr. Hank Carson of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Dr Carson is in charge of monitoring wild geoduck contact harvesting in deep waters, and has no direct involvement in managing intertidal geoduck cultivation. He shares my great concern that there may be harmful impact on the genetic diversity of wild geoduck stocks. We just don’t know the answer to this question, and it is imperative that we stop permitting geoduck farms until we can understand the real impact. This was a strong recommendation of the GARP report.

Potential impacts on the plants and animals of

Henderson Inlet

The Corp of Engineers, the Washington Department of Ecology, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and other agencies are tasked with acting on the behalf of the citizens of the USA and the State of Washington to protect out waters and ecosystems from harmful development. The COE must exercise its authority in the following areas:

Protection of Wildlife: Overview

The interaction between geoduck aquaculture operations and the environment is complex, as outline in this scientific study which models the predicted effects of increasing the biomass of geoduck by 120%. While the authors predicted that the Puget Sound from a “basin scale” approach could handle the extra load of cultivated clams without significant effect related to the extra phytoplankton they would consume, there would be significant impact from the cultivation (non=-trophic) effects.

Evaluating trophic and non-trophic effects of shellfish aquaculture in a coastal estuarine foodweb – Bridget E. Ferriss, Jonathan C. P. Reum, P. Sean McDonald, Dara M. Farrell, Chris J. Harvey

ICES Journal of Marine Science, Volume 73, Issue 2, January/February 2016, Pages 429–440, https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsv173

Published:

13 October 2015

additional article details may be accessed by following the link:

https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/73/2/429/2614240

As you can easily see from the attached table, certain species such as demersal fishes, suspension feeders, and sea urchins can actually increase from geoduck aquaculture, while others, especially shorebirds and predatory gastropods suffer significant losses. Note that an increase in biomass of a species may not be an overall benefit to the environment if that increase produces a secondary impact such as reduction in another species such as from increased predation.

Here is an example of such from this study:

The substantial decrease of most bird groups in the model is important to note, as these are important ecologically, culturally, and socio-economically. A decrease in eagle populations as cultured geoducks increase should benefit other bird groups through release from predation ( Harvey et al ., 2012b ). The biomass of other birds decrease, however, implying bottom-up control in that they have reduced access to key prey (e.g. demersal fish and small crustaceans) due to the predator refuge provided by anti-predator nets on geoduck farms. Migratory shore birds (biomass increase) do not primarily prey upon demersal fish and small crustaceans, and are likely benefiting from a release of eagle predation while not suffering prey depletion. Limited empirical studies have shown both negative and positive interactions between bivalve aquaculture and marine birds ( Kelly et al ., 1996 ; Connolly and Colwell, 2005 ; Zydelis et al ., 2009 ; Coen et al ., 2011 ) in other systems, suggesting that some interactions are likely. Further empirical study is required to understand the relationship between shellfish aquaculture and birds, and validate these results.

It is imperative to note this call for further studies to adequately understand the impact on our ecosystems before allowing further expansion of geoduck aquaculture. This is no adequate cumulative analysis of geoduck aquaculture from repeated use at a far site or development of multiple contiguous sites.

There is never a circumstance where reduction in native bird population up to 20% from an aquaculture project is acceptable. This is a clear violation of the mandate to the Department of Ecology to “protect the wildlife habitat”.

Protection of Wildlife: native geoduck

According to Encyclopedia of Puget Sound

https://www.eopugetsound.org/science-review/1-bivalves

native, wild stock geoduck occur throughout Puget Sound and the greater Northwest at densities of between 0 and 22 clams/square meter, with an average of 1.7. I would submit that from personal experience on the local beach in question, the number is less than 0.5 geoduck/square meter, but will use 1.7 for this discussion.

The densities of planted intertidal geoduck are approximately 3-4 clams/tube x 10 tubes/sq meter, which equals a planted density of 35 clams/sq meter. This is more than 20 times the natural density of geoduck, especially considering the dense planting of contiguous acreage; the number of planted geoduck would be approximately 529,000 for this site alone. As noted above, it has been proven that these intertidal cultivated clams will be reproductively active within 2-3 years, and will interbreed with native clams.

In Effect of Geoduck Aquaculture on the Environment: A Synthesis of Current Knowledge by WA Sea Grant https://marine-aquaculture.extension.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Effects-of-Geoduck-Aquaculture-on-the-Environment.pdf

“Hatchery-reared shellfish may differ genetically from their wild counterparts for multiple reasons”

“wild geoduck populations have high levels of genetic variability that could be perturbed by an influx of cultured genotypes.”

“Even if broodstock are collected locally, hatchery populations may differ from wild

populations owing to random genetic drift or different selective pressures in the hatchery. These differences may reduce the fitness of cultured geoducks and cultured–wild hybrids in the natural environment (Lynch and O’Hely 2001, Ford 2002). As the differentiation between wild and cultured populations increases, the potential for negative genetic interactions between wild and cultured populations increases.”

As discussed under the heading of the GARP study, there is great concern over the possible adverse effect of limited diversity genetics from hatchery stock geoduck clams affecting native stocks through interbreeding. The legislature specifically asked the University of Washington to answer this question with the GARP study and they did not. Will we see degradation of genetic strength in native geoduck similar to the effect of hatchery salmon on wild salmon? Nobody knows the answer to this question, and it is irresponsible to allow this practice without adequate assessment of the impact on native geoduck clams. These stocks are under the protection of the Clean Water Act and the Corp of Engineers must act to protect them.

Protection of Wildlife: Eelgrass

The Washington Department of Natural Resources considers eelgrass so important that it devotes a large section to it on its website.

As noted in the GARP critique section, there are significant safeguards in place to protect eelgrass because of its robust function as a habitat area for fishes, invertebrates, and it supports other species, especially birds. However, significant questions remain about how aquaculture affects eelgrass in Puget Sound.

One of the authors of eelgrass studies in the GARP report, Dr. Jennifer Reusink of the University of Washington writes on her website

https://depts.washington.edu/jlrlab/eelgrass.php

We are examining ways that shellfish and aquaculture practices influence water clarity, sediment characteristics, and benthic habitat structure in Washington estuaries. As a rooted, photosynthetic plant, eelgrass responds to the nutrient and light conditions of its environment. Consequently, aquaculture may have indirect, large-scale impacts on eelgrass, in addition to the local disturbance that can occur during harvest operations. To develop best management practices,  growers need scientific information on these larger-scale impacts, as well as direct small-scale interactions. This information will allow growers to select among culture techniques and distribute impacts in ways that sustain ecologically-important habitats. Applied on a broader estuarine scale, the study will assist managers in understanding the role of filter feeders and designating areas for aquaculture use

growers need scientific information on these larger-scale impacts, as well as direct small-scale interactions. This information will allow growers to select among culture techniques and distribute impacts in ways that sustain ecologically-important habitats. Applied on a broader estuarine scale, the study will assist managers in understanding the role of filter feeders and designating areas for aquaculture use

According to the DNR website, “In Puget Sound the maximum depth to which eelgrass grows can be as shallow as 1 m below the low tide line (MLLW) to greater than 10 m deep. Much of the eelgrass in Puget Sound is subtidal; half the sites sampled for this monitoring program have eelgrass extending to depths greater than 3 m below the low tide line.”

Please note that the submitted documentation for the Mazanti Taylor project site on Johnson Point was prepared by Audry Lamb, an employee of Taylor Shellfish Farms. This was not an independent, verifiable inspection for eelgrass, and should not be accepted by the Department of Ecology or Corp of Engineers. His assessment was done at a -3.18 low tide in July 2019. There is no mention of diving on the site. As stated by the DNR in the above paragraph, eelgrass can grow as deep as 10 meters and is common below 3 meters. While photographs show no obvious eelgrass, the presence of eelgrass has not been excluded at the site. Indeed, native eelgrass is present nearby with over 1 million active plants at nearby Joemma State Park.

The Department of Ecology must not presume that no eelgrass is present at the Mazanti site without requirement for further survey.

Protection of Wildlife: Birds

The following information comes from data collected by the Tahoma Chapter of the Audubon Society in Burley Lagoon, which represents a similar environment to Henderson Inlet.

The Burley Lagoon estuary has for tens of thousands of years been a direct Pacific Flyway zone and stop- over site for non-game and game migratory birds from Alaska and Canada to all parts west of the Continental Divide to Mexico. It was not uncommon to see flocks of hundreds of birds in the wintertime, taking rest and regaining their strength, refueling with food found in abundance in the estuary waters of Burley Lagoon. They often stay for much of the winter, replenishing their energy reserves.

Burley Lagoon is a popular bird watching area for the public, with a checklist of 35 migratory and resident species. These include Common Tern, Black and White Warbler Mallard, Hooded Merganser Downy Woodpecker, Red-breasted Nuthatch, Pine Siskin, Bald Eagle, Horned Grebe, Drake Surf Scoter, Glaucous-winged Gull, Northern Flicker, Brown Creeper barred Owl, Marbled Murrelet (eBird 2018), Double-crested Cormorant White-winged Scoter, Great Horned Owl Crow, American Robin ,Tundra Swans, Osprey, Great Blue Heron, Common Goldeneye, Rufous Hummingbird, Steller’s Jay, Spotted Towhee, Common Loons, Violet-Green Swallow Canada Goose, Common Murre Belted Kingfisher, Black-capped Chickadee, Dark-eyed Junco, Dunlin.

Since 2012 when The Taylor Shellfish Company took over the shellfish farming of Burley Lagoon, residents have witnessed workers removing the top layer of the beach, ridding the beach of the diverse shellfish and invertebrates, flattening out tidal pools that provided a distinct ecological function to the ecosystem, and installing predator nets that deprived shorebirds and migrating birds access to their source of food. Birdwatchers on the Purdy Spit could observe 30-70 Great Blue Herons standing in the small stream at low tide feeding on the crabs and forage fish.

Burley Lagoon DEIS Response (Morse/Wenman/McDonell) Page 41 of 81

Today, only a fraction of those birds visit Burley Lagoon. The noise and light produced by all types of Taylor activities cause observed disorientation and fleeing of birds and marine mammals. And their food sources are substantially depleted. Studies have shown that geoduck culture causes substantial decreases in seabird visits (Ferriss, B. E., et.al., 2016).

Predator Control Netting covers acres of geoduck habitat during grow out – blocking beach soils which feed sea birds. Fine mesh netting prohibits birds from access to muddy areas beneath the netting

This photo documents a bald eagle trapped in a geoduck net, rescued by boaters in 2006. While Bill Dewey of Taylor Shellfish claimed on a recent King 5 news interview https://www.king5.com/video/tech/science/environment/olympia-homeowners-raise-environmental-concerns-over-proposed-geoduck-farm/281-2ddab705-334a-47cb-945b-741f56eb9635 that they now only use mesh tubes in their operations. In fact, Taylopr Shellfish has installed PVC tubes and nets in Henderson Inlet at the Lockhart site in 2023, and applied to use PVC and nets in their current application for the Mazanti lease.

Every additional aquaculture project approved for Henderson Inlet adds pressure on the species of bird that live there, and the cumulative impacts on the estuary must be taken into account.

Protection of Wildlife: Forage Fish

The State of Washington recognized the importance of forage fish and they have codified it in various regulations to protect critical saltwater habitats important to achieving no net loss of ecological functions. The SMP Guidelines state, “Critical saltwater habitats require a higher level of protection due to the important ecological functions they provide” [WAC 173-26-221(2)(c)(iii)(A)]. Critical saltwater habitats include “…all kelp beds, eelgrass beds, spawning and holding areas for forage fish, such as herring, smelt and sand lance; subsistence, commercial and recreational shellfish beds; mudflats, intertidal habitats with vascular plants, and areas with which priority species have a primary association” (WAC 173-26-221(2)(c)(iii)(A)).

The SMP guidelines (WDOE 2015) include specific provisions for aquaculture including: Forage fish spawning habitat is a critical saltwater habitat requiring protection. All aquaculture should be sited outside known forage fish (such as Pacific herring, sand lance and surf smelt) spawning habitat, if possible.

Forage fish are common along the shorelines of Henderson Inlet, and I have personally observed sand lance and herring while snorkeling along the shoreline of Johnson Point Loop. I have also observed spawning surf smelt along these same beaches, where they return every fall in the same way that salmon find their way back to the native streams. The placement of a commercial geoduck operation will significantly impact forage fish during planting and harvesting, and there may be impact from direct ingestion of juveniles migrating away from spawning beds through hundreds of thousands of filter-feeding clams.

Aesthetics

Visual effect

Instead of the pristine shores of Johnson point with gravel beaches, waterfowl, and the occasional raccoon or deer, the observer will see an industrialized shoreline. The proposed geoduck plantation will be highly visible during low tides, along the path of boaters heading along the margins of Johnson Point and crossing to Dana Passage across the mouth of Henderson Inlet. The appearance will be that of a sea of plastic tubes, spaced approximately 1 foot apart, fully 42,000 per acre. Since there are 3.6 acres proposed for development, the residents adjoining this site will see over 150,000 tubes from their back yards. This is what it looks like:

Permits also allow for covering of the fields of tubes with plastic netting, effectively removing the potential for forage by wildlife. Additionally, the development will render the beach inaccessible by locals except for higher tides.

Noise

Complaints due to noise caused by shellfish operations are common; residents of Burley Lagoon have been registering such complaints with Taylor Shellfish and Pierce County for many years. On Johnson Point it is a common complaint from local residents from the wild harvest of geoduck that may be 100s of yards away. The presence of geoduck operations will bring on a new level of noise never before experienced at this site.

Noise pollution is well-known to cause negative impacts and disorientation to marine mammals, birds, and other organisms (Clarke et al. 2009; Rolland et al. 2012; Erbe et al. 2018). The planting and harvesting of geoduck involves the use of a special boat with diesel- powered compressors that pump water into “low-pressure” wands used to place and remove the tens of thousands of PVC of HDPE pipes. This constant mechanical noise and vibration will rob residents and public of the quiet enjoyment of their peaceful neighborhood

Boating, Commerce/navigation

If Taylor Shellfish is granted a permit for this operation, they will by necessity access the site solely by watercraft, meaning markedly increased boat traffic through the area. Recreational boating is prevalent in Henderson inlet; watercraft use consists of speedboats, pontoon craft, jet skis, wake boarders, water skiers, boats pulling children on tubes, kayakers, SUPs, canoes, sailboats, paddleboards, as well as swimmers and fishing activities. Conflicts with local users of these navigable waters will be inevitable. Needless to say, there will be an obstacle course during planting, tube removal, and harvest.

There are no conditions in the proposal to protect recreational users in the area. In fact, a requirement that “buoys with anchors placed intervisibly on any ownership boundary that extends below extreme low tide, for the harvest term” is stipulated in RCW 79.135.200. Also, the U.S. Coast Guard sent a memo to Taylor Shellfish in response to M.L. Schallip, Commander, U.S. Coast Guard, letter of September 28, 2016 referencing reports of vessels striking aquaculture structures and requiring the installation of Private Aids to Navigation (PATON) to mark their operations.

As a resident of adjoining Otis Beach, I commonly swim through this area. I am cautious to stay near the shore and tow a swim buoy of high visibility, as required by law in some areas. If this permit is allowed, I will no longer feel safe swimming along this beach due to the increased and unpredictable boat traffic; the frightening risk of being hit by an incoming aquaculture craft will become too great.

The author swimming on the proposed project tidelands on Johnson Point

Respectfully submitted,

Ron Smith, President

Deb Hall, Secretary

Protect Henderson Inlet

9119 Otis Beach St NE

Olympia, WA. 98516

360-259-3789

Appendix

Full Scientific Reviews

The following three critical reviews of scientific papers that are routinely cited by Taylor Shellfish as supporting the environmental safety of geoduck aquaculture, and are specifically listed on page 2 of their 31 January letter to Thurston County. These reviews are also available at https://protecthendersoninlet.org/ under the heading of SCIENCE.

Critique 1

Effects of Geoduck (Panopea generosa Gould, 1850) Aquaculture Gear on Resident

and Transient Macrofauna Communities of Puget Sound, Washington

Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 34, No. 1, 189–202, 2015

Author(s): P. Sean McDonald, Aaron W. E. Galloway, Kathleen C. McPeek and Glenn R. Vanblaricom

Source: Journal of Shellfish Research, 34(1):189-202.

Published By: National Shellfisheries Association

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2983/035.034.0122

URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2983/035.034.0122

ABSTRACT In Washington state, commercial culture of geoducks (Panopea generosa) involves large-scale out-planting of juveniles to intertidal habitats, and installation of PVC tubes and netting to exclude predators and increase early survival. Structures associated with this nascent (bold added by RS) aquaculture method are examined to determine whether they affect patterns of use by resident and transient macrofauna. Results are summarized from regular surveys of aquaculture operations and reference beaches in 2009 to 2011 at three sites during three phases of culture: (1) pregear (–geoducks, –structure), (2) gear present (+geoducks, +structures), and (3) postgear (+geoducks, –structures). Resident macroinvertebrates (infauna and epifauna) were sampled monthly (in most cases) using coring methods at low tide during all three phases. Differences in community composition between culture plots and reference areas were examined with permutational analysis of variance and homogeneity of multivariate dispersion tests. Scuba and shoreline transect surveys were used to examine habitat use by transient fish and macroinvertebrates. Analysis of similarity and complementary nonmetric multidimensional scaling were used to compare differences between species functional groups and habitat type during different aquaculture phases. Results suggest that resident and transient macrofauna respond differently to structures associated with geoduck aquaculture. No consistent differences in the community of resident macrofauna were observed at culture plots or reference areas at the three sites during any year. Conversely, total abundance of transient fish and macroinvertebrates were more than two times greater at culture plots than reference areas when aquaculture structures were in place. Community composition differed (analysis of similarity) between culture and reference plots during the gear-present phase, but did not persist to the next farming stage (postgear). Habitat complexity associated with shellfish aquaculture may attract some structure-associated transient species observed infrequently on reference beaches, and may displace other species that typically occur in areas lacking epibenthic structure. This study provides a first look (bold added by RS) at the effects of multiple phases of geoduck farming on macrofauna, and has important implications for the management of a rapidly expanding sector of the aquaculture industry.

KEY WORDS: aquaculture effects, benthic community, geoduck, habitat provision, macrofauna, press disturbance, structural complexity, geoduck, Panopea generosa

Introduction

First of all, as with all scientific articles, they must be read in their entirety, not just the abstract which is only an overview and may not fully express the basis for conclusions or the limitations of the study. You may access the full text here.

One of the reasons that I chose this article is that it is one of three articles specifically cited by Taylor Shellfish in their arguments to the Thurston County Planning Commission in 2020 against restrictions being considered on geoduck aquaculture. In the letter from lawyer Dianni Taylor E, she states “These studies demonstrate that, similar to other forms of shellfish aquaculture, geoduck farming does not have significant environmental impacts when properly managed.”

Simply stated, this scientific study proves nothing of the sort, and to characterize it as a key study supporting aquaculture is an extreme distortion. This is why.

Analysis

First, this study was published in 2015 and is based on data collected in 2009-2011, so it’s far from current. What is also important about that is that the authors describe it as a “first look.” To date, there seems to have been no attempt at further looks to corroborate their findings, yet this is considered a key study worthy of being cited in a legal argument? It’s a small study, honestly performed for the most part, but with very limited importance overall. If this were in the field of medicine, these results would never be actionable.

This study gathered data from three different sites, and, although the authors admit that there were significant differences in the sites, they had to be combined to provide enough data to be statistically analyzed.

The study looked at the effect of geoduck aquaculture in three phases, before planting, during planting, and after removal of geoduck tubes, which was roughly 2 years into the cycle. This pointedly ignores the most invasive phase which is the harvest, when hydraulic excavators are used to liquefy the beach as deep as three feet to extract the mature geoduck at age 5-7 years. Ideally, a study would last through a couple of complete cycles, but that would take a lot more time. Funding tends to be limited, and there is usually pressure at universities to publish, so there might not have been much of an incentive to extend the study.

It’s not much of a surprise that most of the mobile species (not all) increased around the structure of the tubes. I think any 3rd grader with a fishing pole knows that fish are attracted to structure, but in science, we do have to prove things. That said, they may have proved something, but an increase in some species does not allow the conclusion that there is no significant impact (a conclusion of the lawyer, not the scientist), and the lack of carrying the study through the harvest phase relegates this paper to a role of minor importance in my opinion.

The following is important: in their analysis, they identified 68 different taxa (species). However, their analysis only included 12 species, which they called the most important ones, but didn’t really say why they were the most important ones. It seems that they were the only ones for which they had enough data to analyze. Let’s think about that for a minute. 12 species of 68 is less than 18%. They made their conclusions based on a fraction of the species present, excluding in their design anything mobile less than 6 cm long, without an explanation of why these 12 were important. By analogy, consider the Serengeti with its wildness and large population of mammals. If you chose importance by abundance, what would that say about the value of lions in the ecosystem when there might be 1000 times the number of wildebeests? In all ecosytems the interdependence of species is of paramount importance and this study seems to ignore that basic question in order to draw a conclusion from the limited data that they had available. Admittedly, observing a hooved mammal might be a great deal easier than identifying small creatures in the tidelands while scuba diving through murky water, but such is the task they outlined for themselves.

There were no significant sightings of salmonids, so they appropriately excluded them from analysis. What? No conclusions about salmon in a landmark study?

This brings up a somewhat tangential subject, but the absence of salmon smolts reminds me that the control sites (a control is a separate area of study supposedly unaffected by whatever parameters are being looked at in the main study area, used for comparison) that were used as a standard in these research studies are far from what was present historically at these sites. The Olympia oyster once covered 70% of Salish Sea tidelands, reduced to only a tiny fraction of that now. If there was a true standard to compare, and the impact being measured was on a beach covered with native oysters, the impact of the implanted geoduck tubes and the subsequent observations would likely be far greater. Sadly, we now only have degraded ecosystems. Among many other species, out-migrating salmon including the endangered Chinook, would use native Olympia oyster beds as forage ground if those beds had survived. It is important to remind ourselves that the control areas used in these and all similar studies are already degraded. Best to refer to them as reference areas, as no true controls are available anymore. The truth of it is that, sadly, the scientists don’t have much of a choice here.

Finally, I have a real problem with this statement in the authors introduction – “Projection of future aquaculture production to meet human food demands imply an expanding ecological footprint for these activities in nearshore environments.” Whether good or bad, this is a true statement regarding shellfish aquaculture in general, but this is a study about panopea generosa, the geoduck. We don’t eat them. We sell them abroad where they are consumed as an expensive delicacy. They are unnecessary, generally unavailable to the local consumer, and unimportant as a food source in the impacted area where they are grown. The authors inflate the importance of this study with such a statement. I also have a problem with the use of the word “nascent” in the abstract, which appropriately means beginning to be formed, but also has implications of a promising enterprise. The promise happens to be purely financial.

I would be interested in knowing what the authors think about the importance of this study relative to the big questions facing us about expanding aquaculture, especially about whether they endorse the use of their papers by Taylor Shellfish and others to support this expansion.

Critique 2

ECOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF THE HARVEST PHASE OF GEODUCK (PANOPEA GENEROSA

GOULD, 1850) AQUACULTURE ON INFAUNAL COMMUNITIES IN SOUTHERN PUGET

SOUND, WASHINGTON

Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 34, No. 1, 171–187, 2015

GLENN R. VANBLARICOM, 1,2 * JENNIFER L. ECCLES, 2 JULIAN D. OLDEN 2 AND

P. SEAN MCDONALD 2,31U.S. Geological Survey, Washington Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, College of the Environment, University of Washington, Mailstop 355020, Seattle, WA 98195-5020; 2School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, College of the Environment, University of Washington, Mailstop 355020, Seattle, WA 98195-5020; 3Program on the Environment, College of the Environment, University of Washington, Mailstop 355679, Seattle, WA 98195-5679

ABSTRACT Intertidal aquaculture for geoducks (Panopea generosa Gould, 1850) is expanding in southern Puget Sound, Washington, where gently sloping sandy beaches are used for field culture. Geoduck aquaculture contributes significantly to the regional economy, but has become controversial because of a range of unresolved questions involving potential biological impacts on marine ecosystems. From 2008 through 2012, the authors used a ‘‘before–after-control-impact’’ experimental design, emphasizing spatial scales comparable with those used by geoduck culturists to evaluate the effects of harvesting market-ready geoducks on associated benthic infaunal communities. Infauna were sampled at three different study locations in southern Puget Sound at monthly intervals before, during, and after harvests of clams, and along extralimital transects extending away from the edges of cultured plots to assess the effects of harvest activities in adjacent uncultured habitat. Using multivariate statistical approaches, strong seasonal and spatial signals in patterns of abundance were found, but there was scant evidence of effects on the community structure associated with geoduck harvest disturbances within cultured plots. Likewise, no indications of significant ‘‘spillover’’ effects of harvest on uncultured habitat adjacent to cultured plots were noted. Complementary univariate approaches revealed little evidence of harvest effects on infaunal biodiversity and indications of modest effects on populations of individual infaunal taxa. Of 10 common taxa analyzed, only three showed evidence of reduced densities, although minor, after harvests whereas the remaining seven taxa indicated either neutral responses to harvest disturbances or increased abundance either during or in the months after harvest events. It is suggested that a relatively active natural disturbance regime, including both small-scale and large-scale events that occur with comparable intensity but more frequently than geoduck harvest events in cultured plots, has facilitated assemblage-level infaunal resistance and resilience to harvest disturbances.

KEY WORDS: aquaculture, benthic, disturbance, extralimital, geoduck, infauna, intertidal, Panopea generosa, Puget Sound, spillover

Critique

As in all scientific papers, the reader is encouraged to evaluate the entire article, which can be found here.

This study was published in 2015, based on data collected between 2008 and 2012. It seeks to determine whether there is a significant effect of a commercial geoduck operation on benthic (in the beach) organisms by comparing samples before, during, and after the harvest phase. Samples were obtained from three sites which were so different that the data from each of these sites had to be evaluated separately. “Such an approach had the unavoidable effect of reducing statistical power for detection of significant differences.” Nevertheless, the data was analyzed using multivariate and univariate methods, the latter described this way: “Some components of our data failed to meet underlying assumptions on which ANOVA (ed. a method of statistical analysis using one variable) methods are based.”

So, what about that data? In this study 50 taxa (species) were identified in samples. They chose to evaluate the 10 most abundant ones, citing reasons for inclusion based on behavior in the ecosystem for only one of those species. So, only 20% of the identified species were evaluated other than a gross measurement by weight. Please see my discussion about the problem of this approach in critique 1. There is no discussion of the importance or lack thereof for the other 40 species. Their final conclusion was that there was no significant effect of the geoduck aquaculture project, but along the way they state “Of the 10 most frequently sampled infaunal taxa, only 3 indicated evidence of reduction in abundance persisting as long as four months after conclusion of harvest activities.” The math is pretty easy here. 30% of the most common species show reduction in numbers, in their view, not significant? But rest assured, the three did not “approach local extinction.”

So, the conclusion is that there wasn’t much effect, but there are also many disclaimers. They point out that, it was hard to find good sites to study, that the sites were relatively isolated and being used for geoduck for the first time, and that patchy harvest could significantly affect the data. Also, the long-term effects were unknown. “The data may not provide sufficient basis for unequivocal extrapolation when a given plot is exposed to a long series of successive geoduck aquaculture cycles. Likewise, it may not be appropriate to extend the findings of the current study to cases when a number of separate plots are adjacent to one another, and encompass significantly larger surface area than any single plot.” In other words, they can’t really say what might happen in practice.

The authors conclude with “resolution of the questions of larger special spatial and temporal scales will be a major challenge for geoduck farmers as they continue production on existing plots and expand into new areas, and will be an important research goal in the interest of informed management policies by natural resource agencies.”

There has been no attempt that I am aware of to reproduce or further evaluate these findings with follow-up studies as of July 2023, particularly with regard to the potential cumulative effects of geoduck aquaculture.

This, like the scientific paper in critique 1, is not a landmark study, and I think that it does not have the power to guide major policy decisions. It honestly attempts to draw conclusions based on limited data, and appropriately disclaims the results. It is a gross mischaracterization by the shellfish industry to say: “These studies demonstrate that, similar to other forms of shellfish aquaculture, geoduck farming does not have significant environmental impacts when properly managed.” (Quote Diani Taylor E in a letter to the Thurston County Planning Commission 25 November 2020).