A Presentation Considering Washington State’s Native Oyster: the Olympia

In our mission to protect, preserve, and restore the inlet, PHI remains steadfast against harmful policies, practices, and propaganda. Our priority, however, lies with learning and sharing about the inlet’s still vibrant natural life and contributing to efforts to reverse loss.

To that end, we are honored to have the acquaintance of Washington State’s lead in restoring the Olympia Oyster, Dr. Julietta Martinelli. She enthusiastically agreed to share information with our organization about current restoration efforts in our state. On October 29th, 2024, she met us at Olympia’s Harbor House to present a public overview of restoration efforts. The following is a summary of what we learned.

George Watlund of the Sierra Club was our co-host. Under the roof of the Harbor House, shaped like a Coast Salish Canoe bow, Dr. Martinelli explained that a large population of our native oyster has thrived here for tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years.

The thick band of Olympia Oyster shells near Willapa Bay in the next photo dates to the Pleistocene Era.

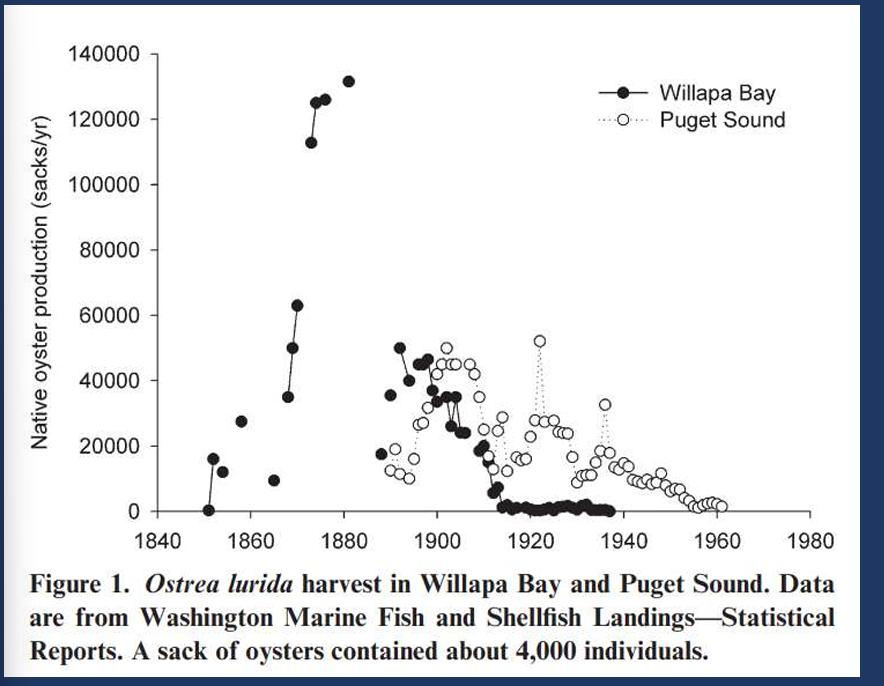

In more recent times, following the colonization by European Americans, Olympia Oysters played a part in positioning Olympia as our state capital. Demand for the oysters grew, especially with trains that could transport them in a timely manner. Olympia Oysters were heavily harvested in Puget Sound from about 1890 to 1962. Peak production reached almost 55,000 bags a year in the early 1920s, with each bag holding approximately 4000 oysters.

Overharvesting, along with the negative effects of pollutants from such sources as pulp mills, led to the near extinction of the Olympia Oyster. Today’s population hovers at only around 4% of historic levels.

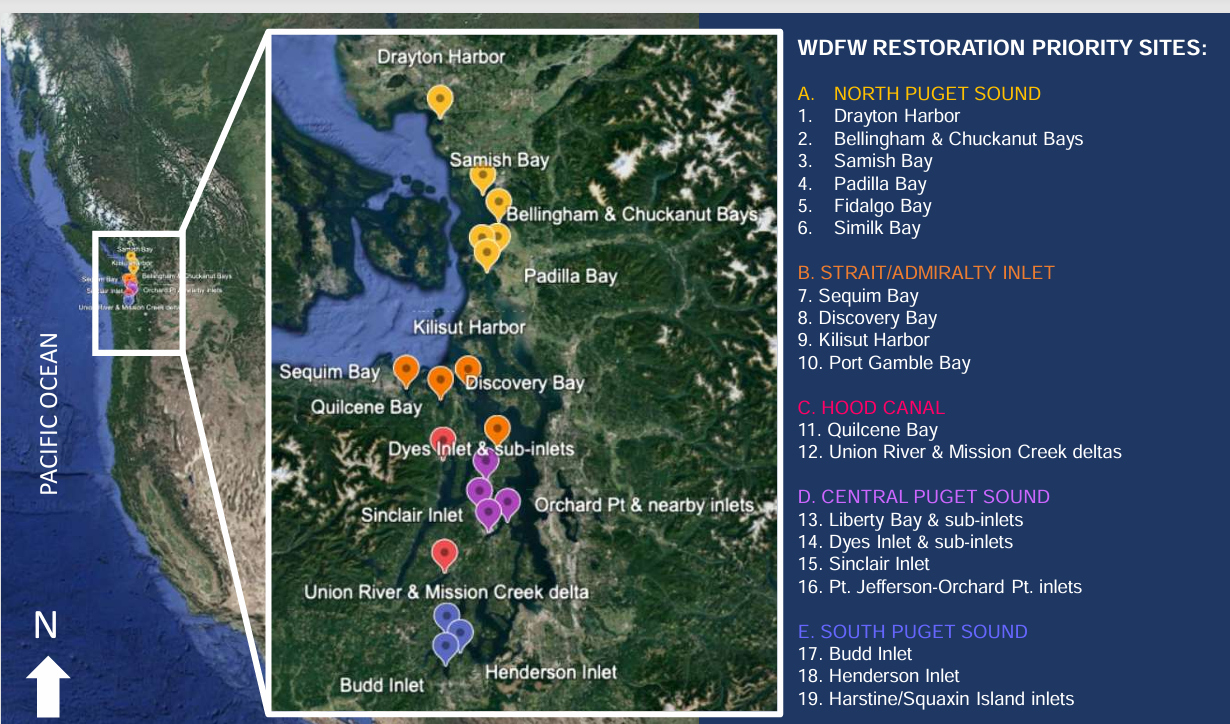

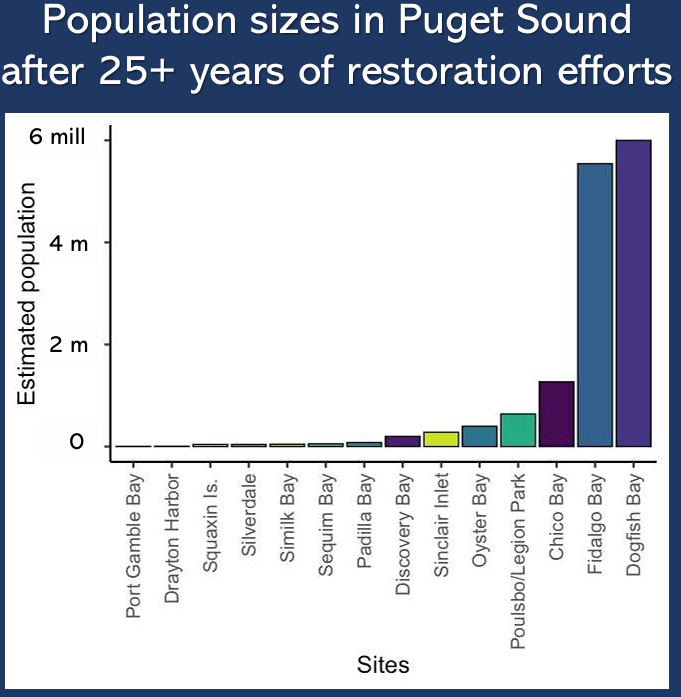

Our state has been involved with restoration efforts for twenty-five years now. The WDFW currently studies nineteen priority sites within five sub-basins, including Meyers Point in Henderson Inlet.

Olympia Oysters from each of the five sub-basins appear to be genetically distinct which could prove to be an important factor. Genetic diversity demands further study.

The hatchery at Kenneth Chew Center in Port Orchard produces a lot of seed, but not all of it is usable because the genetics of what is grown there only match oysters in the North Sound. If released into the other sub-basins, they could potentially harm what remains of the Olympia Oysters already there. Whether restoring by adding spat-on shell larvae and/or singles, or adding shells to enhance the substrate, or doing both, having enough of what is believed to be the correct seed is a limiting factor.

To learn more about oysters in a given area, recruitment stations (stacked Pacific oyster shells on wooden dowels) are set out in early summer when Olympia oysters spawn. The recruitment stations are collected in the fall. One weak link is that there aren’t enough trained people to count and classify the oysters that settle on each shell face. The backlog of uncounted recruitment stations is years long. Not being able to track the information from the collected recruitment stations promptly also limits progress.

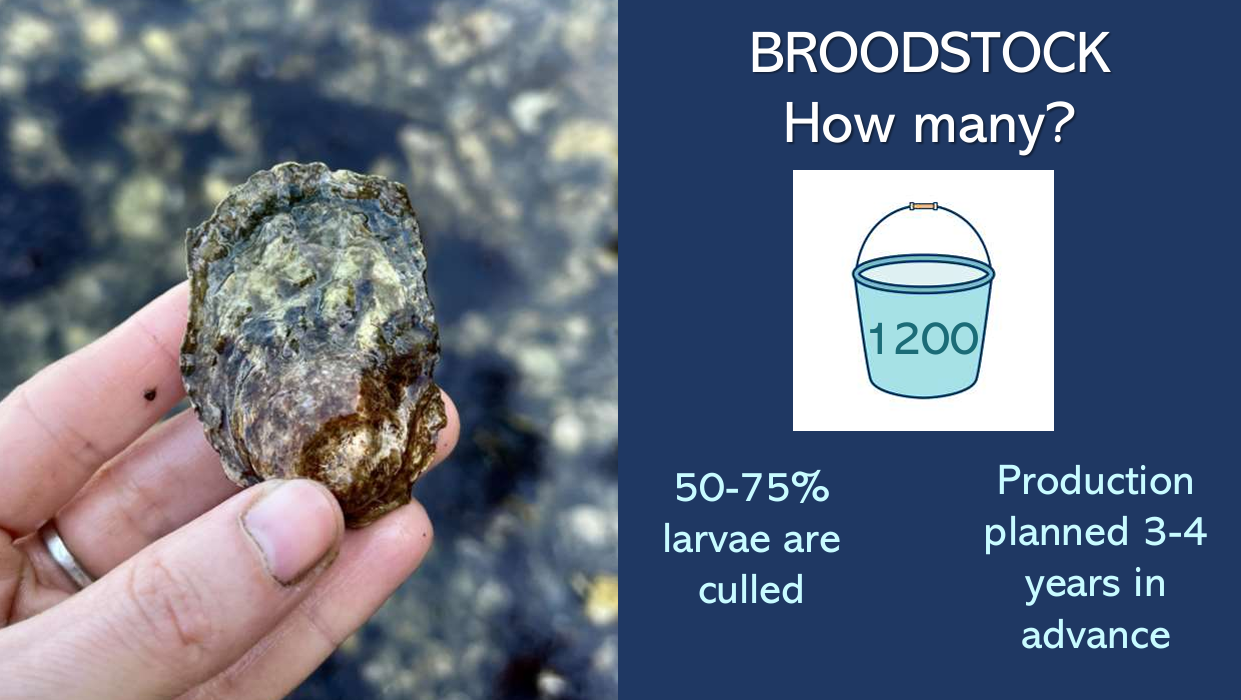

The broodstock formula for reproducing seed is to cull 50-75% of the larvae from a given site, but many of the sites currently have very small populations. It is important to question whether taking 50-75% of the larvae could deplete already imperiled populations and how much broodstock is enough to preserve the population structure.

Predators such as the Japanese Oyster Drill are problematic too. Japanese Oyster drill also eats barnacles, so providing the drill with an abundance of barnacles may help save Olympia Oysters.

Next steps include genotyping 550 individual oysters from the West Coast and interpreting and sharing the findings.